An understanding of target learners

Here I will outline how learning technology is instrumental in me being able to meet the needs of learners on ‘day courses’ where pre-course diagnostic tests are not possible, how I use diagnostic information when available to meet learners’ needs and how use of a co-evaluation, co-design process puts learners in the ‘driving seat’ of curriculum design.

Please also see cross-cutting evidence on use of hybrid learning for widening participation in portfolio section 3a.

Meeting needs on one-off, day courses

As a core part of my identity as a teacher educator I consider that I have an obligation to be a role model for accessible, inclusive pedagogy. This strategy is also especially important to me as I personally facilitate a significant number of one-day workforce development courses for diverse organisations which offer no opportunities to diagnose or discuss learners’ needs beforehand. Often, I meet learners for the first time when they arrive in the learning space for the start of the session and am with them for only six or seven hours.

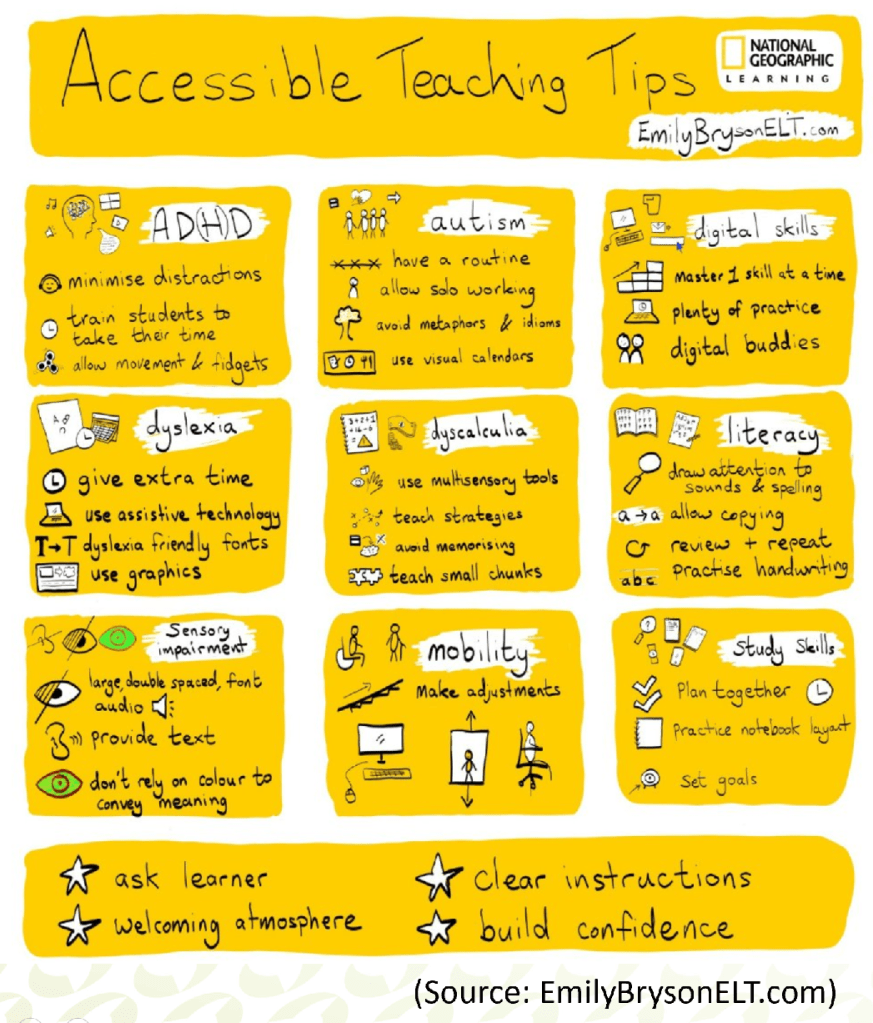

Use of learning and assistive technologies are instrumental in allowing me to model inclusive, accessible learning to teacher educator learners. I ensure that I design learning resources to be adaptable to meet a range of learners needs and also model how learners can adapt their own resources.

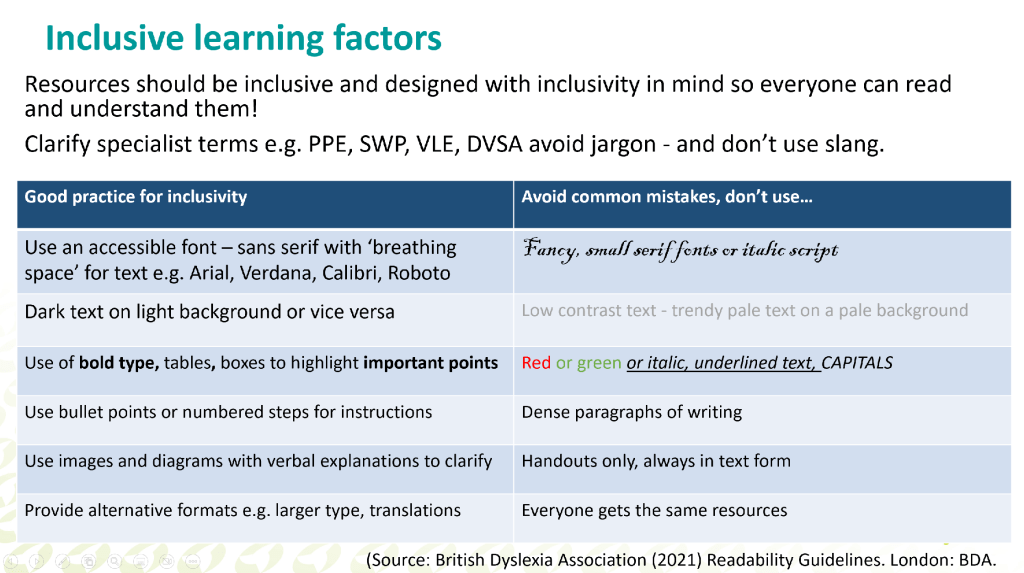

I model and share resources created using style guidelines from the British Dyslexia Association, and AbilityNet, discuss accessible learning principles and demonstrate tools such as Mercury Reader for removing adverts and distractions from web-based content. I also show learners how to adjust font size, background colour and text colour in a range of common documents. I also model the use of ALT text for online image, and speech-to-text and dictation tools for use with text-based resources. Regarding feedback on assignment tasks, I model and use Mote. I find that learners appreciate personalised, verbal comments on their work and listening to feedback often allows them to appreciate empathetic nuances such as tone and inflections that may be lost in text-only feedback.

Below I have provided examples of a couple of the resources that I use in teacher education to encourage new teachers to ensure that they create resources with inclusivity and accessibility in mind.

Identifying needs and providing support on longer programmes

When working on longer form curriculum, such as the initial teacher training course the Award in Education and Training, I have opportunity to use more sophisticated diagnostics to establish and meet learners’ support needs. All participants are encouraged to complete BKSB online diagnostics in English and maths before beginning the programme which give a great deal of useful information on their entry skills.

I find that learners split into two typical profiles, the first being highly qualified individuals from professional business contexts such as HR who often have Masters or Doctoral qualifications, the others being vehicle drivers and warehouse operatives, who are highly skilled in their occupational setting but have often left school with few formal qualifications. Some may require more extensive support, particularly with the writing of formal essays or reports for the course.

The BKSB online diagnostics give us an overall skills picture, but I prefer to also get a piece of word-processed writing from all participants as soon as possible as part of their first assessment. This gives me the opportunity to review how they set out an essay and appraise skills with spelling, punctuation and grammar, then provide them with feedback via in-margin comments:

Once the learners have reviewed these I use on-demand online tutorials via Zoom to support their writing and referencing development. I find that simple strategies such as showing learners how they can logically order a narrative by using different colour highlighting on topics which should be grouped together demonstrated live on screen with a verbal explanation of the writing technique is popular and successful.

I also extensively use Mote to provide audio comments where learners have successfully achieved criteria and made valuable points and also where they require development in skills such as sentence construction or spelling. Mote audio comments allow me to reinforce in-text comments and provide more nuanced explanations of the complexities of English language, which can often be necessary when differentiating between words such as ‘their’, ‘there’ and ‘they’re’. I supplement these comments with links to related educational videos from YouTube such as the series from Discovery Education (an example can be seen here on use of the apostrophe) as I find these can really bring the use of parts of speech and grammar vividly to life.

Using a co-design, co-evaluation approach to meet learners’ needs

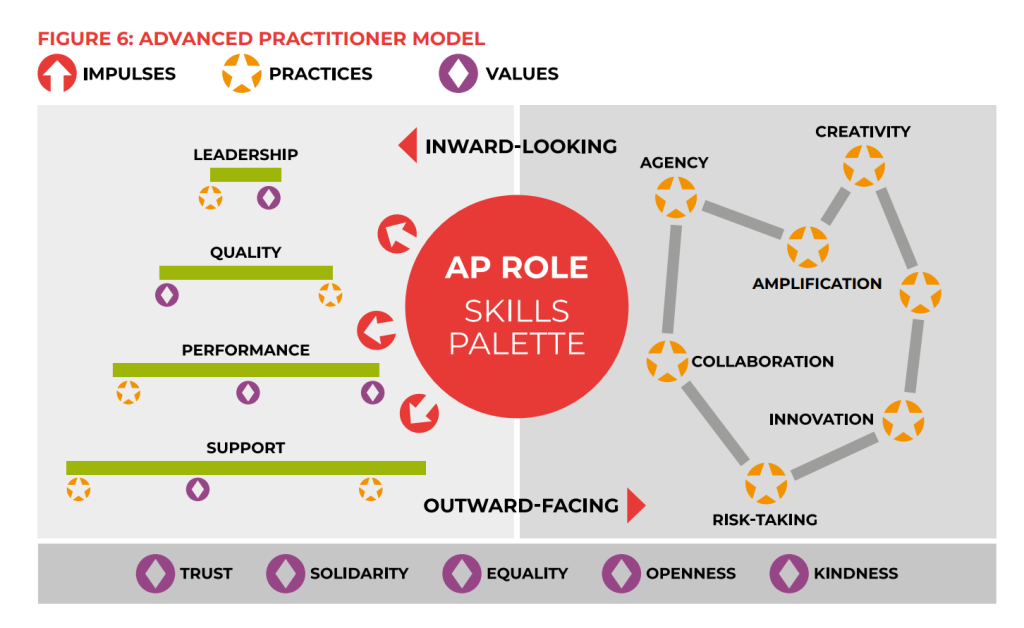

Another way I ensure that I am identifying and meeting learners’ needs is by using a process of curriculum co-design and co-evaluation. As a curriculum and learning platforms designer for the DfE/ETF/touchconsulting APConnect programme in 2021-22 I was part of a core team involved in the curriculum co-design process where, again, technology played a pivotal role.

The programme was in its fourth year and had always encouraged critical evaluation from participants with feedback being collected mid-year and at the end of the programme. In the fourth year a new approach was adopted using Zoom webinars, a Slack channel and Google Forms to allow continuous feedback to be collected from participants and immediately acted upon and to refine the programme in progress and to produce a co-designed model representing the Advanced Practitioner identity and role.

The methodology we used was adapted from a research circle approach (Bergman, 2014). This is rooted in the idea that the success of an evaluation and its ability to produce useful knowledge increases when the work is connected to the core values and aims of participants and an ethos of trust is fostered which allows open dialogues.

My work involved leading webinar breakout rooms and establishing a Slack channel in which a group of volunteer co-evaluators came together for a regular series of online, face-to-face webinars and participated in dialogues as the evaluation and model were devised and developed. The meetings discussed the impact that the programme had in supporting Advanced Practitioners towards their vision for advanced practice in their organisations and how we could refine the programme to better fit participants’ needs.

Critical evaluation data was collected during four virtual ‘milestone Evaluation Circles’, and five ‘sub-circle’ events and evidence captured on shared a Wakelet collection. The evaluation circles allowed participants and the programme design team to reflection upon how participants’ understanding of their AP role was developing and allowed the team to decide upon ‘actionable knowledge’ (Holmstrand et al., 2017) which could be used to refine the programme.

In immediate, practical terms, we used evaluation feedback to move from a themed, asynchronous group ‘action research model’ using online discussion forums (which had been somewhat effective in the first three years of the programme), to live Tuesday and Friday drop-in webinar support events. These included ‘Try It Here First’ sessions where participants could trial a new technology or learning strategy in a ‘safe space’ with colleagues and Thinking Environment (Klein, 1998) sessions where participants could discuss progress and potential next steps related to live projects underway in their organisations.

The co-evaluation produced powerful findings, led by participants, for use in the longer term, which concluded that future AP work needed to:

- Revisit how the AP role is framed and ‘sold’ in organisations so that a shared understanding of the role in different FE and Skills contexts is built

- Revisit the role that middle managers and senior leaders play in supporting APs examining how institutional hierarchies support them

- Examine the potential for co-evaluation methodologies to be further developed in quality improvement initiatives to fully recognise the value an place of co-evaluation approaches.

The co-evaluation process also led to a co-designed model of the Advanced Practitioner ‘Skills Palette’, developed during the webinar meetings using outline sketches which were refined live using annotation on the Zoom shared whiteboard. This allowed the team to develop the outline sketch model created in the webinars into the final version shown below.

As a final outcome of the co-evaluation and curriculum co-construction, the APConnect team authored a final report which provides a broader outline of the co-evaluation methodology, tools, process and findings, ‘Rethinking the Role of the Advanced Practitioner’ (Donovan et al, 2021):

Reflection

When I reflect upon the impact that learning technology has had upon my practice as a teacher and teacher educator, I think the most profound impacts can be seen in improvements made to accessibility, inclusivity and meeting the needs of learners. The affordances of learning technology allow me to ensure that I work from the outset with resources designed with accessibility and learners’ needs in mind. I can then further use technology as each learner’s unique support needs emerge during longer programmes and engage learners in a curriculum co-design and co-construction process more effectively.

Having facilitated learning in FE for over 20 years, I began using printed acetates on a desk-mounted projector, giving little option to consider adaptable, inclusive resources. By leveraging all of the tools available in current learning technology I am now able to change almost every aspect of the digital and online resources I use in my practice, allowing huge adaptability in resource provision. Ensuring that learners are also aware of these options and tools gives them agency to adapt resources to better suit their own needs and to use technology to be more independent and resilient as individuals.

I still find that a real challenge with respect to accessibility are the bad examples still set by some major organisations, sadly, many in learning provision or education management. We still regularly encounter use of classic low visibility text (such as use of red and green type to accent ‘do’ and ‘don’t’) or elaborate, serif fonts on many official documents. When we encounter these in the learning space I make a point of asking learners how they would edit using accessibility guidelines so that they get into the habit of critically reviewing every document and website they encounter or create themselves with an ‘accessibility eye’.

Learning technology has also revolutionised how I conduct assessment and feedback. The ability to provide live, on-demand online tutorials and audio feedback has certainly revolutionised my ability to provide personalised support. I find the difference between written and verbal feedback is striking. Less confident learners might read a text-based sentence putting a ‘pessimistic spin’ onto it, particularly when they have had negative experiences in learning spaces in the past. By using audio feedback I am able to convey far more subtle nuances in intonation, and therefore in meaning, ensuring that my feedback is positive, motivational and received as intended.

Probably the most exciting impact of learning technology use is the ability to effectively enter into a collaborative programme co-design and co-evaluation process with learners. Tools such as shared whiteboards on Zoom, shared online documents, Google Form feedback and Slack dialogue spaces have removed the need for geographical proximity or synchronous communication. This has allowed learners from all over the country and with different time and day availabilities to participate fully in live curriculum construction and evaluation.

A move from the more traditional, single end-of-course evaluation, which allowed no proactive, in-course curriculum refinement, to continuous co-design means that learners are truly able to feel ownership of a course and exercise agency in its direction and provision. I feel that this has been key in meeting adult learners’ needs and is certainly something that I am now embedding more extensively into my practice, encouraging the teams and the new teachers that I work with to do the same.

References:

Bergman, L. (2014) The Research Circle as a Resource in Challenging Academics’ Perceptions of How to Support Students’ Literacy Development in HE. Canadian Journal of Action Research. 15. 3-20.

British Dyslexia Association (2020) Dyslexia friendly style guide. [online] Available from: https://cdn.bdadyslexia.org.uk/uploads/documents/Advice/style-guide/Dyslexia_Style_Guide_2018-final-1.pdf?v=1554827990. Accessed on 28/08/2022.

Donovan, C., Forrest, C,. Braidwood, D., Crowson, S-J., Mycroft, L., White-Lambert, S.,Latif, S,. Salt, S., Taylerson, L. and Zahariea, M. (2021)

Re-thinking the role of the Advanced Practitioner: AP Connect Year 3 Evaluation Strand Final Report. Burton-on-Trent: touchconsulting Limited for ETF.

Holmstrand, L., Härnsten, G. and Löwstedt, J. (2017) The Research Circle Approach: A Democratic Form for Collaborative Research in Organizations. London: Sage.

Kline, N. (1998) Time to Think: Listening to Ignite the Human Mind. London: Cassell.