Understanding and engaging with policies and standards

For cross-cutting evidence on my work with Equality, Diversity and inclusion / SEND standards, please also refer to portfolio element 2b and on Sustainability / Education for Sustainable Development Community of Practice please refer to Core Area 4, Communication and Working with Others.

The ETF Professional Standards (2022)

The most significant set of standards which impact on my practice as a teacher and teacher educator are the Education and Training Foundation Professional Standards for Teachers and Trainers (2022).

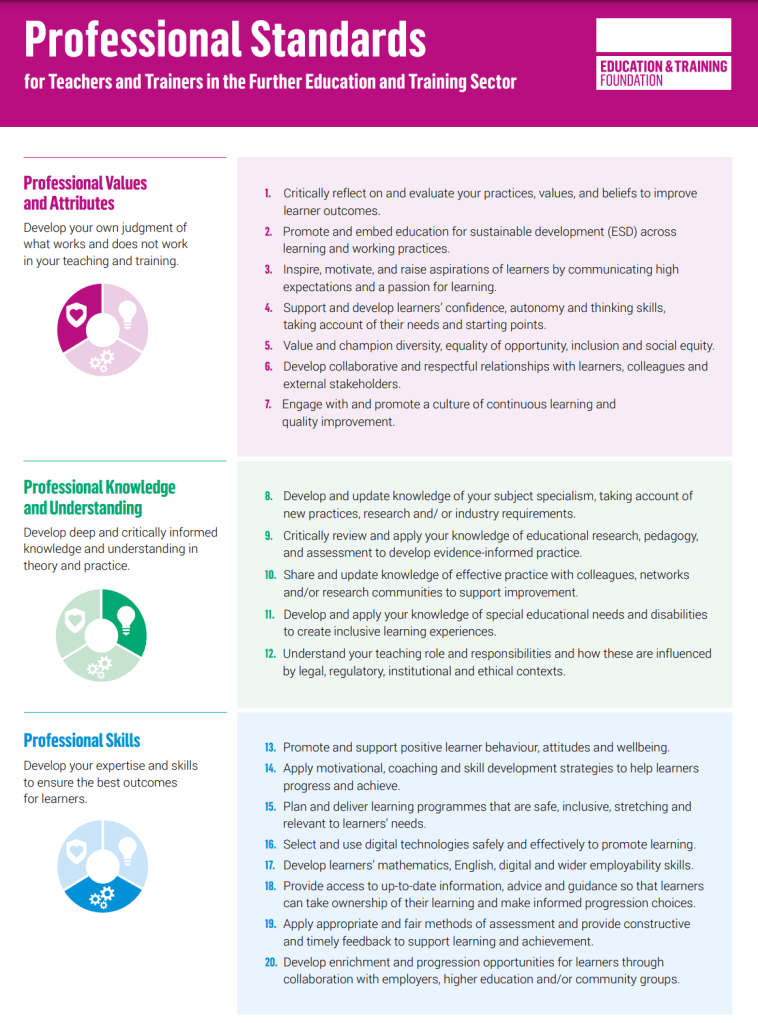

The Standards consist of 20 ‘aspirational statements’ organised into three domains of practice, ‘Professional Values and Attributes’, ‘Professional Knowledge and Understanding’ and ‘Professional Skills’:

I use the 20 standards to evaluate my own practice and plan my professional learning. I also use them to guide me when I am observing new educators in the sector as part of an initial teacher training qualification where they provide useful headline statements for dialogues around session planning and facilitation and professional practice and researcher identity development.

I have embedded references to the Professional Standards throughout my initial teacher training curriculum and encourage new and experienced teachers and their leaders and managers to use them in self-reflection when planning individual, departmental and whole-organisation CPD.

Below is an example resource from the Award in Education and Training module ‘Professional Roles and Responsibilities’ showing updates to reflect the new 2022 standards:

As well as using the Standards in my daily practice I also had significant involvement in their authoring. I was part of the ETF / Pye Tait consultation which drew up the ETF Standards in their original form in 2014, when they replaced the outgoing FENTO Standards.

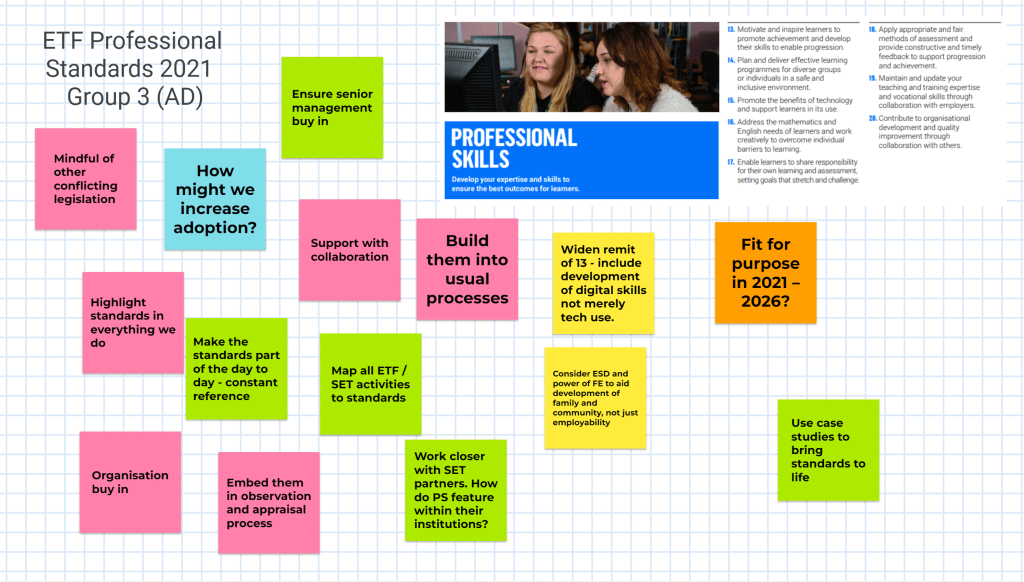

As part of the Society for Education and Training’s Practitioner Advisory Group (SET PAG) I also had significant input into the consultation on the new, reframed standards which were launched in Spring 2022 and their subsequent initial evaluation. My involvement came first as a contributor to the consultation focus group webinars in summer and autumn 2021, which used Google Jamboard (see image below) to gather opinions and suggestions from the SET PAG focus group.

When the new Standards were in draft form I was involved in their evaluation and final updating as part of my PAG role. Finally, I helped to launch and promote the Standards to the sector in Spring 2022 in a series of video, audio and social media promotion activities:

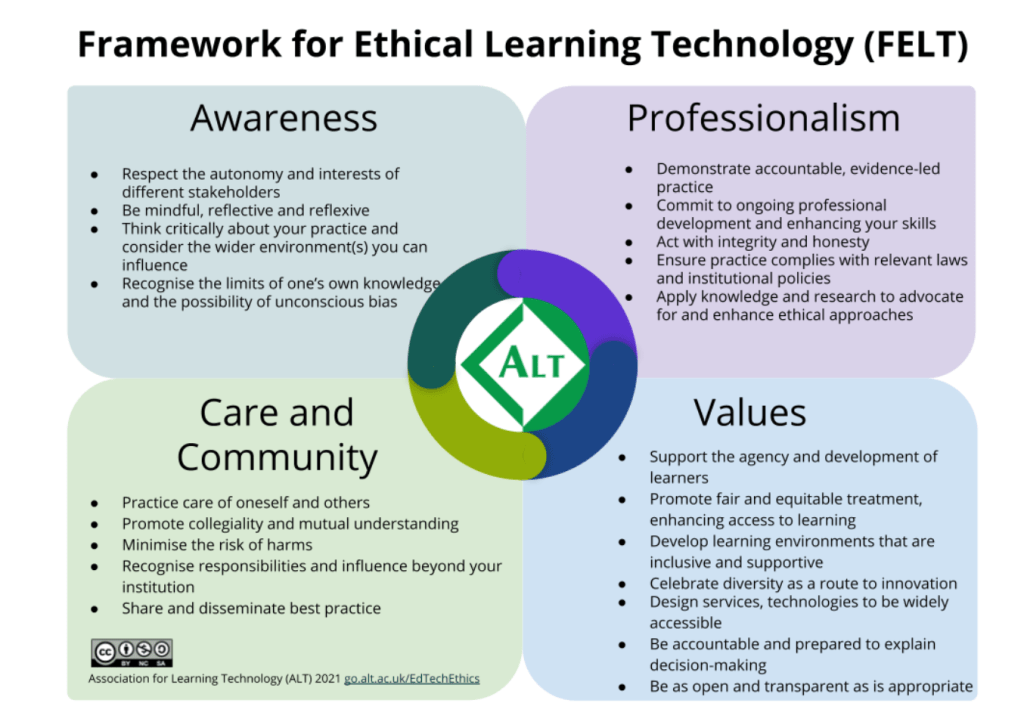

ALT’s FELT Ethical Framework

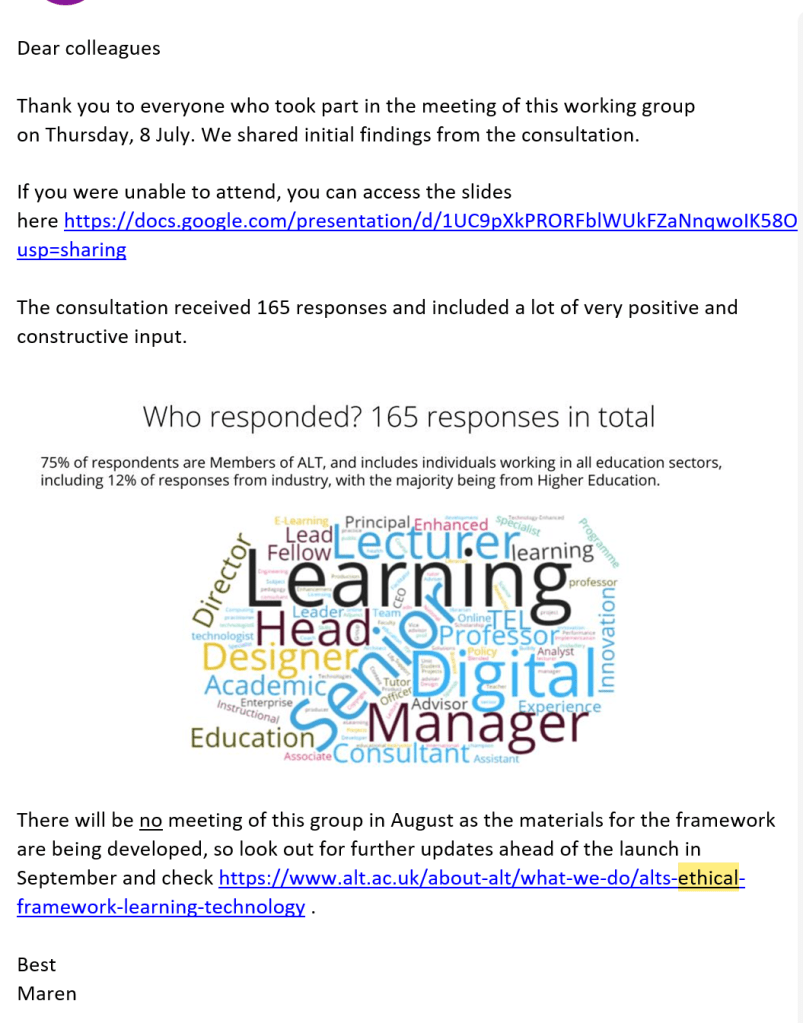

Another important framework that I participated in the creation of as a member of the Working Group was ALT’s ‘Framework for the Ethical use of Learning Technology’ (FELT) which was launched at the ALTC annual conference in 2021:

My role was to attend and participate in working group dialogues and also to participate in online reviews and commentary on the framework and the case studies used to develop and promote it as the work evolved:

Now the framework is established I find it a very useful foil to the ETF Standards with respect to use of learning technology and digital systems and development of digital skills in FE. I have referred to FELT when working with organisations to launch and embed virtual learning environments and when working in teacher education to empower educators in the sector to use learning technology and digital tools more extensively.

I find FELT’s focus on inclusive values and ‘Practices of Care’ are particularly valuable resources to draw on when promoting the design of accessible, inclusive resources when working with trainee and new teachers. FELT guidelines are also useful and when discussing cyberbullying, ‘digital overwhelm’, ‘digital overload’ and the negative impacts on wellbeing that misuse or overuse of online systems can cause with both FE teachers and learners.

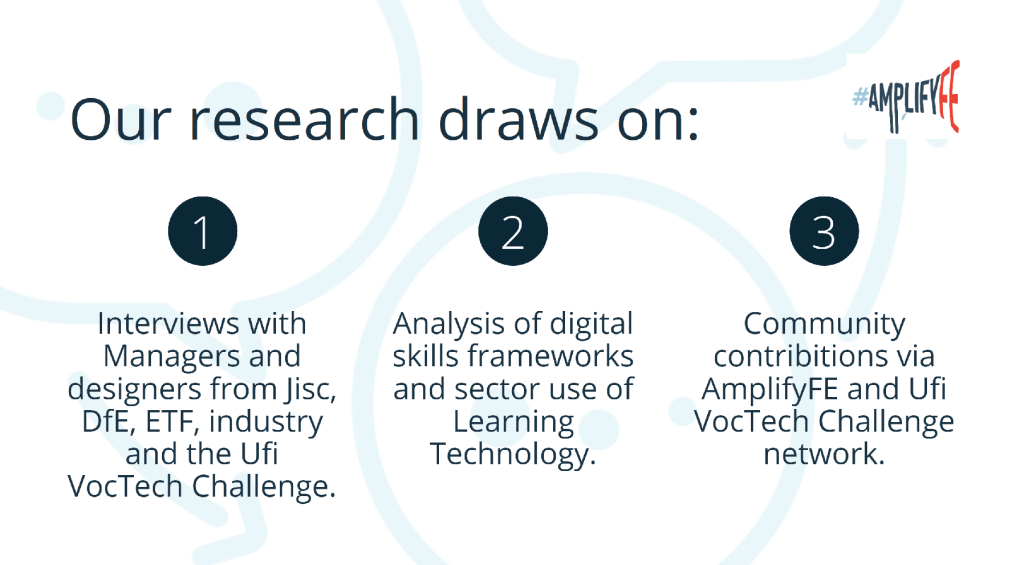

I also drew on the FELT framework extensively in recent research work for ALT/Ufi’s ‘AmplifyFE’ on designing and deploying learning technology to narrow the digital divide in vocational education which will be published in Autumn 2022 and is detailed in this portfolio’s Advanced Area :

The ’Open Movement’ and ‘Open Philosophy’

A third framework which deserves a mention in this section is the Open Movement and accompanying Open Philosophy. As an independent learner, not affiliated to or enrolled with a college or university, and therefore not having access to the extensive digital libraries available to students at larger institutions, Open resources are vitally important to me, and those in a similar position. Equally, as a teacher educator one of the greatest frustrations for me is watching teachers ‘reinventing the wheel’ every year, creating resources from scratch around common curriculum areas such as health and safety, communication skills or essay writing when excellent, freely available, easily adaptable resources already exist.

These are two reasons why I actively promote Open Educational Commons resources (OER) to learners and colleagues. I also promote other open platforms such as the extensive repository of learning resources available on SlideShare, the book chapters and articles available on ResearchGate and the open courses available on platforms such as FutureLearn or OpenEd the University of Edinburgh’s OER open online collection made freely available ‘for the common good’.

I believe that for an Open Philosophy to truly work, we must instil in everyone the ethos that they must ‘give as well as receiving’ so that everyone can benefit to the maximum from Open assets. When my work is not covered by copyright or intellectual property restrictions (which it is when working for many clients) I ensure that it is openly licenced. I made my PhD thesis and other journal articles, blogs and conference presentation assets freely available under an Open Licence via ResearchGate allowing others to reuse or re-mix them freely. I also practice an ‘informal open philosophy’ so where I have created useful slides, for example for venue housekeeping, group ground rules, academic writing or other ubiquitous topics in education, I share these freely with students on demand.

Reflection:

Policies and standards clearly have an important place in the practice of learning technologists. When reflecting on the value and use of standards I tend to divide them in my mind into two categories, the first being technical standards (for example operating parameters for devices or platforms, OER) the second being what we might describe as professional practice standards (which tend to be behavioural and attitudinal in nature). The former tend to be precise and deliberately less nuanced in nature, phrasing or deployment, the latter can be more contentious in respect to how they are received and used as they seek to guide how we behave in our professional lives and interactions.

Professional standards clearly prove useful as a roadmap to teachers’ professional learning and an aid to reflective practice, yet I feel there is a danger that frameworks such as ETF’s Professional Standards may be used as the basis of a ‘CPD menu’ by leaders and managers in some organisations and consequently as a ‘tick box achievement list’ by some teachers or quality representatives. Standards can also be used in some organisations as a ‘deficit model’ to describe what is missing or falls short in an educators’ practice, rather than as an aspirational growth-promoting tool.

I agree with Kennedy’s (2005) analysis that we need to ask where power and control lie when creating and implementing professional standards. She suggests standards-led CPD models lie on a spectrum from a ‘transmission’ process, passing on pre-ordained ‘best practice’, via a professional straightjacket, to ‘transformational’ development where teachers use agency to steer the direction of their development using standards as an aspirational tool (ibid:17).

Reflecting on the differences in the consultation processes and outcomes for the 2014 and 2022 ETF Standards, I think it’s pleasing to note how a journey from transmissive to transformational standards is being followed. enabled in the most part by technology use.

The 2014 Standards had much to commend them, replacing the unwieldy 43-page FENTO Standards which were, in my experience, little used except in ‘tick box’ quality exercises. The original consultations for the 2014 Standards, from my perspective, placed employers and universities (who then steered teacher education curricula) firmly in the driving seat. The consultation events I attended were largely populated by university personnel with too few representatives from the FE sector.

This use of independent industry experts and employability-focussed metrics aligns with Kennedy’s training model (2005:4) Teachers ‘strive to demonstrate particular skills specified in a nationally agreed standard’, a ‘technocratic view’ centred on demonstration of competence. Training is ‘delivered’ to teachers by ‘experts’, to an agenda ‘determined by the deliverer’ with teachers in a passive role.

The resulting 2014 Standards, to my mind, put focus heavily on two areas, first the chief role of FE being to prepare learners for the workplace, what Biesta calls ‘learning for earning’ rather than what I and I hope many other educators would consider a core purpose of education, the growth and ‘welfare of all’ (2015:81). The second focus was to ensure that teachers engaged deeply with learning theory and educational research activities, as any university naturally expects. I would consider this activity important, yet lower on the agenda for most FE teachers and leaders. I also harboured other concerns regarding the treatment of the role of technology in learning in the 2014 Standards.

Kennedy (2005:9) considers that standards ‘provide a common language, making it easier for teachers to engage in dialogue’ but need to be designed and deployed in the spirit of ‘collaborative and collegiate learning’, respecting teachers’ ‘capacities for reflective, critical inquiry’ (ibid:10). The 2022 Standards consultation put FE teaches back in the ‘driving seat’ by using a sector-wide online consultation heavily involving the SET PAG members, all of whom are currently active in sector educator or leader roles.

We see significant changes in the resulting 2022 Standards, which I believe are more beneficial to agentic professional learning and to FE teachers’ core identity and values. There is clear acknowledgement that FE benefits, and works in partnership with, the individual and their community as well as with employers for the benefit of the economy. We also see the introduction of the sustainability (ESD) agenda in a new standard with specific focus on education for sustainable development. There is also a timely, more significant focus on the importance of wellbeing of learners and teachers and an embedding of ethical principles as well as legal ones, something which links well to ALT’s FELT framework regarding technology use.

From a learning technologists’ perspective I think the most significant change in the new Standards comes in the treatment of learning technology and digital tools. Only one standard in the 2014 suite touched on the use of technology, that being number 15, ‘Promote the benefits of technology and support learners in its use’. While it was welcome to see use of technology in learning acknowledged, I felt that the phrasing saw teachers provided with technology then placed in a leaders’ role supporting subordinate learners, where, in reality we see many learners working in partnership with teachers to explore technology as many learners have advanced skills and are naturalised users of digital networks.

The rephrased standards related to technology are:

5. Select and use digital technologies safely and effectively to promote learning, and

6. Develop learners’ mathematics, English, digital and wider employability skills.

I think it is a welcome development to suggest teachers exercise agency to select the technologies they use and to have a statement on safe usage. It is also good to see the acknowledgement of the need for a suite of ‘techno-mathematical literacies’ in standard 6. Digital skills are viewed here as underpinning and empowering English, maths and employability skills, an idea working in parallel with the DfE’s ‘General English, Maths and Digital Competencies’ the skills framework for the new T Level qualifications.

One criticism I have of standard 5 is that I would have liked it to include a specific mention of development of informed digital pedagogy alongside digital technology use. This would firmly acknowledge a specific place for criticality in the choice of digital tools and approaches and the growing body of digital learning theory that teachers can draw upon when developing as nuanced users of learning technology.

That aside, it is encouraging to see increased focus on culture, values, ethics and wellbeing and the importance of community and teacher agency in the 2022 standards. These are principles that firmly underpin both the Open Standards and ALT FELT framework also discussed here. Kennedy (2005:4) would agree: professional standards, and the CPD resulting from their use, must connect with the ‘essential moral purposes’ at the ‘heart of professionalism’ for teachers.

References:

Biesta, G. J.J. (2015) What is Education For? On Good Education, Teacher Judgement, and Educational Professionalism. European Journal of Education, Vol. 50, No. 1, 2015.

Education and Training Foundation (ETF) (2022) Professional Standards for Teachers and Trainers. London: ETF.

Kennedy, A. (2005) Models of Continuing Professional Development: a framework for analysis. Journal of In-service Education, Volume 31, Number 2, 2005.

Return to SCMALT portfolio home page